In order to design behaviors or

controllers for, for robots, we inevitably

need models of how the robots actually

behave. And we're going to start with one

of the most common models out there, which

is the model of a differential drive

mobile robot. So, differential drive

wheeled mobile robot has two wheels and

the wheels can turn at different rates and

by turning the, the wheels at different

rates, you can make the robot move around.

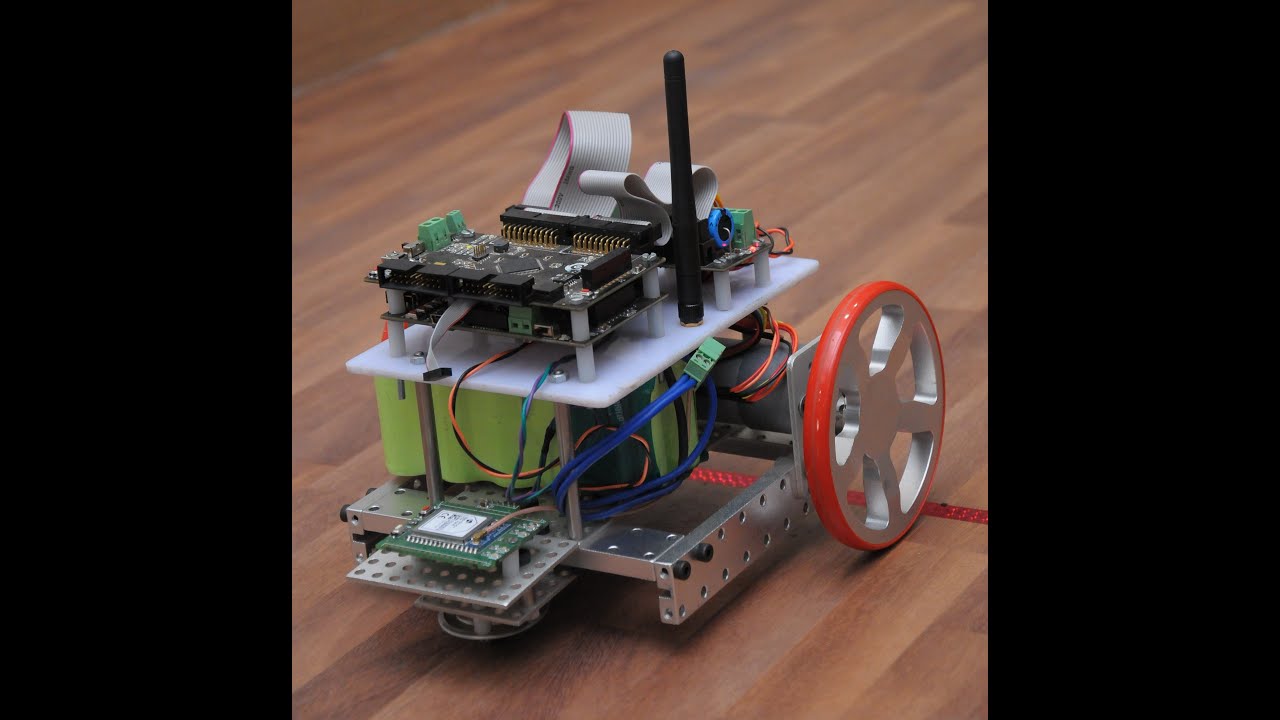

So, this is the robot we are going to

start with and the reason for it is

because it is extremely common. In fact,

the Khepera 3, which is the robot that we

are going to be using quiet a lot in this

course is a differential drive wheeled

mobile robot. But a lot of them out there

are, in fact, differential drive robots.

Typically, they have the two wheels and

then a caster wheel in the back. and the

way these robots work is you have the

right wheel velocity that you can control

and the left wheel with velocity that you

can't control. So, for instance, if

they're turning at the same rate, the

robot is moving straight ahead. If one

wheel is turning slower than another, then

you're going to be turning towards the

direction in which the slower wheel is.

So, this a way of actually being able to,

to make the robot more round. So, let's

start with this kind of robot and see what

does a robot model actually look like.

Well, here's my cartoon of the robot. The

circle is the robot and the black

rectangles are supposed to be the wheels.

The first thing we need to know is what

are the dimensions of the robot. And I

know I've said that a good controller

shouldn't have to know exactly what

particular parameters are because

typically dont know what the friction

coeficcient is. Well, in this case, you

are going to need to know two parameters.

And one parameter you need to know is the

wheel base, meaning how far away are the

wheels from each other? We're going to

call that L. So, L is the wheel base of

the robot. You're also going to need to

know the radius of the wheel, m eaning how

big are the wheels? We call that capital

R. Now, luckily for us, these are

parameters that are inherently easy to

measure. You take out the ruler and you

measure it on your robot. But these

parameters will actually play a little bit

of a role when we're trying to, to design

controllers for these robots. Now, that's

the cartoon of the robot. What is it about

the robot that we want to be able to

control? Well, we want to be able to

control how the robot is moving. But, at

the end of the day, the control signals

that we have at our disposal are v sub r,

which is the rate at which the right wheel

is turning. And v sub l, which is the rate

at which the left wheel is turning. And

these are the two inputs to our system.

So, these are the inputs, now, what are

the states? Well, here's the robot. Now,

I've drawn it as a triangle because I want

to stress the fact that the things that we

care about, typically, for a robot is,

where is it, x and y. It's the position.

And which direction is it heading in? So,

phi is going to be the heading or the

orientation of the robot. So, the things

that we care about are where is the robot,

and in which direction is it going? So,

the robot model needs to connect the

inputs, which is v sub l and v sub r, to

the states, somehow. So, we need some way

of doing this transition. Well, this is

not a course on kinematics. So, instead of

me spending 20 minutes deriving this,

voila, here it is. This is the

differential drive robot model. It tells

me how vr and vl translates into x dot,

which is, how does the x position of the

robot change? Or to y dot, which is how is

the y position, or phi dot, meaning how is

the robot turning? So, this is a model

that gives us what we need in terms of

mapping control inputs onto states. The

problem is, that it's very cumbersome and

unnatural to think in terms of rates of

various wheels. If I asked you, how should

I drive to get to the door, you probably

not going to tell me how what v sub l and

v sub r are, your probably g oing to tell

me don't drive too fast and turn in this

direction. Meaning, you're giving me

instructions that are not given in terms

of v sub l and v sub r, which is why this

model is not that commonly used when

you're designing controllers. However,

when you implement them, this is the model

you're going to have to use. So, instead

of using the differential drive model

directly, we're going to move to something

called the unicycle model. And the

unicycle model overcomes this issue of

dealing with unnatural or unintuitive

terms, like wheel velocities. Instead,

what it's doing is it's saying, you know

what, I care about position. I care about

heading, why don't I just control those

directly? In the sense that, let's talk

about the speed of the robot. How fast is

it moving? And how quickly is it turning,

meaning the angular velocity? So,

translational velocity, speed, and angular

velocity is how quickly is the robot

turnings. If I have that my inputs are

going to be v, which is speed, and omega,

which is angular velocity. So, these are

the two inputs. They're very natural in

the sense that we can actually feel what

they're doing which, we typically can't

when we have vr and vl. So, if we have

that, how do we map them on to the actual

robot. Well, the unicycle dynamics looks

as follows, x dot is v cosine phi. The

reason this is right is, if you put phi

equal to 0, then cosine phi is 1. In this

case, x dot is equal to v, which means

that your moving in a straight line, in

the x-direction, which makes sense.

Similarly for y, so y dot is v sine phi

and phi dot is omega because I'm

controlling the heading directly or the,

the, the, the rate at which the heading is

changing directly. So, this model is

highly useful, we're going to be using it

quite a lot which is why it deserves one

of the patented sweethearts. Okay, there

is a little bit of problem though because

this is the model we're going to design

our controllers for, the unicycle model.

Now, this model is not the differential

drive wheele d model, this is. So, we're

going to have to implement it on this

model and now, here we have v and omega.

These are our, the, the control inputs

we're going to design for. But here, v sub

r and v sub l are the actual control

parameters that we have. So, we somehow

need to map them together. Well, the trick

to doing that is to find out that this x

dot, that's the same as this x dot, right?

They're the same thing. This y dot is the

same as the other y dot. So, if we just

identify the two x dots together, then

divide it by cosine 5, we actually get

that the velocity v is simply r over 2, v

sub r plus v sub l or 2v over r is vr plus

vl. So, this is an equation that connects

v, which is the translational velocity or

the speed, to these real velocities. And

we do the same thing for omega. We get

this equation. So, only l over r is vr

minus vl. Now, these are just two linear

equations, we can actually solve these

explicitly for v sub r and v sub l and if

we do that, we get that v sub r is this

thing and v sub l is this other thing. But

the point now is, this is what I designed

for, this is what I designed for. So, v

and omega are design parameters. l and r

are my known measured parameters for the

robot, the base of the robot, meaning how

far the wheels are apart, and the radius

of the wheel. And with these parameters,

you can map your designed inputs, v and

omega, onto the actual inputs that are

indeed running on the robot. So, this is

step 1, meaning we have a model. Now, step

2 is, okay, how do we know anything about

the world around us?

EmoticonEmoticon